Spot the Pest, Stop the Damage

This technology is a standardized field-recognition guide whose goal is to avoid confusion with look-alike pests by using clear visual markers (the inverted “Y” on the head, sawdust-like frass deep in the whorl) and simple verification steps; a grassroots early-warning workflow that lets extension agents confirm new Fall armyworm sightings quickly; and a misdiagnosis-prevention measure that requires side-by-side checks with maize stem borers, cutworms, and other armyworms before any advice or spraying, thereby reducing unnecessary pesticide use.

This technology is pre-validated.

| Gender Groups | Positive Impact |

|---|---|

| Women Smallholder Farmers |

|

| Rural Youth & Young Agripreneurs |

|

| Low-Income Rural Households (Intersects with women/men/youth in poverty) |

|

| Women-Led Cooperatives and Associations |

|

Climate adaptability: Highly adaptable

Accurate, early identification ensures farmers can detect pest surges in real time. This provides the agility needed to cope with climate-driven pest spread (as warmer temperatures influence FAW life cycles). An informed community can rapidly respond and adjust management timing based on observed pest pressure.

Farmer climate change readiness: Significant improvement

By protecting crops from damage via early detection and action, the technology provides a crucial buffer that stabilizes production. This helps ensure farmers harvest something even during climate-stressed seasons (e.g., drought or floods), which otherwise would compound yield losses. The knowledge provides the adaptive trait necessary to manage pests whose patterns are becoming less predictable due to climate change.

Biodiversity: Positive impact on biodiversity

Accurate ID minimizes the use of broad-spectrum insecticides, which otherwise kill non-target organisms like pollinators and natural enemies (e.g., parasitoid wasps, predator ants). This judicious action protects the functional biodiversity of the field, fostering a more balanced agro-ecosystem where natural checks on FAW can thrive. Scouting also teaches farmers to conserve natural enemies by recognizing signs of parasitism or disease.

Carbon footprint: A bit less carbon released

By preventing panic spraying and ensuring timely, targeted interventions, identification reduces unnecessary pesticide applications. Fewer redundant pesticide applications lead to a lower carbon footprint associated with agrochemical manufacturing, transport, and application.

Environmental health: Greatly improves environmental health

Correct diagnosis prevents the misuse or overuse of hazardous chemicals. This reduces the overall chemical load in the environment, mitigating risks of pesticide poisoning incidents and contamination of air and soil. The emphasis on biological and cultural controls (which ID enables) aligns with sustainable intensification.

Soil quality: Does not affect soil health and fertility

Identification enables the prioritization of IPM practices that are beneficial to soil health. By reducing chemical use, the technology protects the soil microbiome. Furthermore, ID enables cultural controls (like intercropping, conservation agriculture, and proper residue management) that improve soil structure, nutrient cycling, and water retention—key factors for healthy soils.

Water use: A bit less water used

Reduced chemical runoff into water bodies occurs when accurate identification guides farmers away from widespread, indiscriminate spraying. This protects aquatic biodiversity and reduces contamination of ground and surface water. Scouting (ID) is often coupled with good agronomic practices that encourage water use efficiency (e.g., timely planting to avoid drought periods or mulching).

The integration of Fall Armyworm (FAW) identification technology into a government project or program is primarily a knowledge-transfer strategy, grounded in standardized training and public awareness. Since the core resource is the Fall Armyworm Field Handbook: Identification and Management (FAO/CABI, 2019), a critical resource that is open access and widely disseminated, government action should focus on leveraging this foundational document for nationwide capacity building.

The following are the Key Points to Design Your Program for a government integrating only FAW identification capacity:

The government must formally anchor the identification protocol within the national agricultural structure to ensure consistency across all extension and field operations.

Capacity building requires mass training and ensuring the right tools are available to the right personnel at the local level.

Identification is the core input for a functional early warning system; the government must create robust pathways for reporting and verification.

To achieve long-term impact, the government must sustain the knowledge system and build public trust in the information provided.

Open source / open access

Scaling Readiness describes how complete a technology’s development is and its ability to be scaled. It produces a score that measures a technology’s readiness along two axes: the level of maturity of the idea itself, and the level to which the technology has been used so far.

Each axis goes from 0 to 9 where 9 is the “ready-to-scale” status. For each technology profile in the e-catalogs we have documented the scaling readiness status from evidence given by the technology providers. The e-catalogs only showcase technologies for which the scaling readiness score is at least 8 for maturity of the idea and 7 for the level of use.

The graph below represents visually the scaling readiness status for this technology, you can see the label of each level by hovering your mouse cursor on the number.

Read more about scaling readiness ›

Uncontrolled environment: validated

Common use by intended users, in the real world

| Maturity of the idea | Level of use | |||||||||

| 9 | ||||||||||

| 8 | ||||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Gender Groups | Positive Impact |

|---|---|

| Women Smallholder Farmers |

|

| Rural Youth & Young Agripreneurs |

|

| Low-Income Rural Households (Intersects with women/men/youth in poverty) |

|

| Women-Led Cooperatives and Associations |

|

| Target groups | Unintended Impact | Mitigation Action |

| Women Smallholder Farmers |

|

|

| Rural Youth & Young Agripreneurs |

|

|

| Low-Income Rural Households |

|

|

| Women-Led Cooperatives and Associations |

|

|

|

Target Groups |

Barriers to Adoption |

Mitigation Measures |

|

Women Smallholder Farmers |

|

|

|

Rural Youth & Young Agripreneurs |

|

|

|

Low-Income Rural Households |

|

|

|

Women-Led Cooperatives/Associations |

|

|

| Country | Testing ongoing | Tested | Adopted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This technology has not been tested or adopted in any country. | ||||

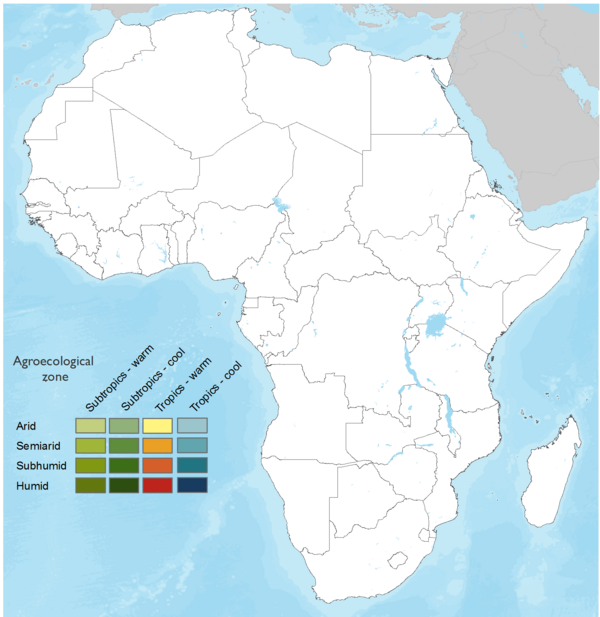

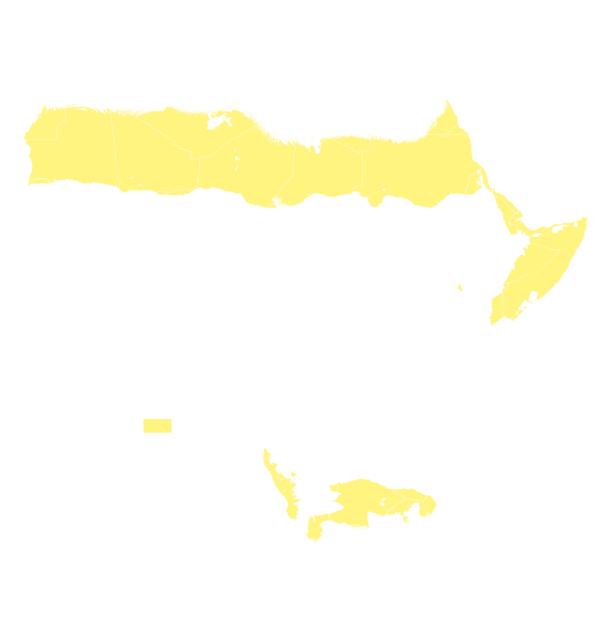

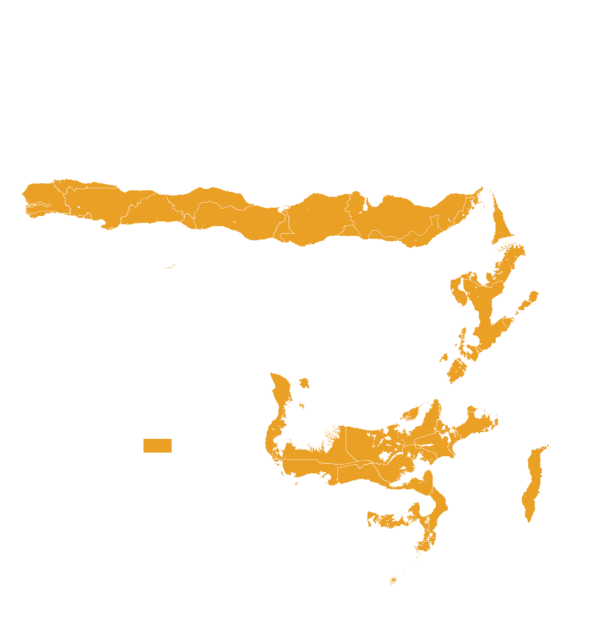

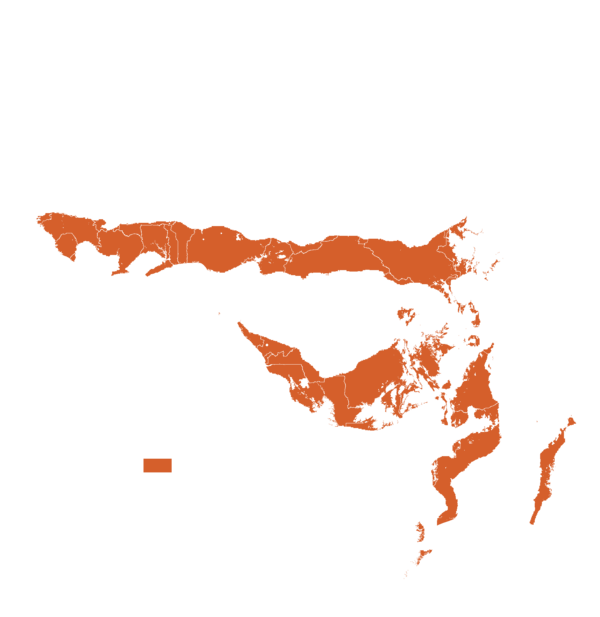

This technology can be used in the colored agro-ecological zones. Any zones shown in white are not suitable for this technology.

| AEZ | Subtropic - warm | Subtropic - cool | Tropic - warm | Tropic - cool |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arid | – | |||

| Semiarid | – | |||

| Subhumid | – | |||

| Humid | – |

Source: HarvestChoice/IFPRI 2009

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals that are applicable to this technology.

Accurate and early identification of FAW helps protect maize and other staple crops from severe losses. Timely detection ensures that farmers can initiate control measures (either mechanical, botanical, or chemical) before damage escalates, which translates directly into more stable yields and improved food security for households.

Accurate pest diagnosis promotes safer pest management practices. When farmers confidently identify FAW, they are less likely to misuse or overuse hazardous pesticides out of panic or confusion with other pests. This directly reduces human exposure to toxic chemicals (lowering poisoning incidents) and contributes to overall health outcomes in rural farming communities.

Empowering farmers with correct pest identification (e.g., distinguishing FAW by its inverted "Y" mark) is the essential first step toward judicious use of agricultural inputs. Farmers apply control measures more responsibly, typically only spraying when thresholds are met and when it is confirmed to be FAW, avoiding wasteful consumption of pesticides and fostering sustainable crop production.

The knowledge-based identification system strengthens climate adaptability. As climate change alters pest patterns, an informed farming community using standardized ID tools can detect these shifts in real time and quickly adapt management strategies. By enabling low-impact controls, it also lowers the carbon footprint associated with agrochemical manufacturing and transport.

Early and accurate identification is crucial for environmental stewardship. By preventing unnecessary or widespread use of broad-spectrum insecticides, the technology spares beneficial insects (such as parasitoid wasps and pollinators) and soil fauna from collateral damage. This preservation of functional biodiversity helps maintain a balanced agro-ecosystem that naturally keeps FAW and other pests in check.

The procedure for Fall Armyworm (FAW) identification focuses on examining the pest's physical markers, life stages, and feeding evidence to accurately distinguish it from other caterpillars found on maize. This knowledge is crucial for triggering timely and correct control actions.

The steps to identify FAW are as follows:

Begin by closely examining the caterpillar itself, using visual guides or hand lenses if available, focusing on these unique morphological traits:

Examine the plant, especially the newest leaves and the whorl (funnel), for unique feeding signs left by the caterpillars:

Confirmation can often be made by identifying other stages of the FAW life cycle:

It is vital to confirm that the insect is indeed FAW and not another pest, as misdiagnosis can lead to applying the wrong control method.

If uncertainty remains, technology and simple tools can assist in final confirmation:

Last updated on 10 December 2025